They Sent Men in Black Suits to Take the ‘Blind’ Boy From My Cabin. They Laughed at My ‘Folk Magic.’ A Year Later, His Billionaire Father Returned… But What He Said Next, and the Miracle That Followed, Still Haunts Me.

Part 1

The October air in the Cascades has a bite that gets in your bones. It’s a wet, penetrating cold, and it’s the first thing I remember about that day. The second is the silence.

I’m Emily. I live with my Grams in a cabin that’s been in our family for four generations, tucked so deep in the woods that the government census taker gets lost every decade. We live off the grid. We grow our own food, we chop our own wood, and we heal our own. Grams is a master herbalist, and I’m her apprentice. We’re the people the locals come to when the sterile white walls of a clinic feel colder than the sickness.

That day, I was checking my traplines—for rabbits, not… not for people.

The woods were dead silent. Too silent. Even the jays were quiet. That’s a bad sign. It means a predator is near. I figured a cougar, maybe a bear. I slid my skinning knife from its sheath on my belt, my heart thumping a low, steady drum against my ribs.

I smelled the creek before I saw it, and that’s when I saw him.

He was just… standing there. On the slick, moss-covered rocks by the water’s edge. He couldn’t have been more than ten. And he was wrong. Everything about him was wrong.

He was wearing a coat that looked like it cost more than our truck. It was a sleek, black, quilted thing. His shoes were shiny, patent leather, now caked in mud. He was porcelain pale, his dark hair plastered to his forehead by a cold sweat.

But it was his eyes. God, his eyes.

They were open, staring straight ahead, but they were off. Like the power was cut. They were empty, flat, lifeless. He was staring, but he wasn’t seeing.

“Hey,” I called out, my voice sounding too loud in the stillness. “Hey, kid! Are you okay?”

No response. Not a twitch. Not a blink.

I moved closer, slow, like you would with a spooked deer. “Kid? Can you hear me?”

I was ten feet away. Five feet. I waved my hand in front of his face. Nothing. He just stood there, trembling, a tiny, involuntary tremor racking his small body. His lips were blue.

“Oh, God,” I whispered. “You’re freezing.”

I touched his hand. It was like ice. A block of ice.

I looked around. No one. No parents, no hikers, no car. Just the endless, quiet woods. Who leaves a child like this? A blind child?

“Okay,” I said, more to myself than to him. “Okay, we’re going home.”

I grabbed his icy hand. “My name is Emily. I’m going to help you. We’re going to my cabin. It’s warm.”

He flinched at my touch, a violent, full-body jerk, but he didn’t pull away. He was so stiff. I had to gently, physically, turn his body and guide him. He walked like an automaton, his expensive shoes stumbling on the roots and rocks. I practically had to carry him the last half-mile.

When I burst through the cabin door, Grams looked up from the woodstove, a cast-iron skillet in her hand. Her face, usually a roadmap of gentle wrinkles, hardened.

“Emily? Who in God’s name…?”

“Found him by the creek, Grams,” I panted, maneuvering the rigid boy toward the hearth. “He’s frozen. And… Grams, I think he’s blind.”

Grams, ever the pragmatist, didn’t ask more questions. “Get those wet things off him. Now. I’ll get the mullien and comfrey.”

We worked fast. We stripped off the absurdly expensive, soaking-wet clothes. Underneath, he was just a skinny little kid, all ribs and sharp angles. His skin was mottled. We wrapped him in three of our thickest wool blankets and sat him by the fire.

Grams came back with her supplies. She gently turned his face to the light. “No,” she said softly, peering into his empty pupils. “The eyes are clear. This ain’t a physical blindness, Em. This is in his head. Something… something broke him.”

A different kind of chill went down my spine, one that had nothing to do with the weather.

Grams was surprised, but she knew what to do. She lived by one code: you help who’s in front of you. She recognized instantly that this child needed more than a hospital. He needed care.

I gently lit the oil lamps, casting a warm, flickering glow against the wood-paneled walls. Grams pulled her remedies from the dried bunches hanging from the rafters. She took dried calendula and soothing chamomile, steeping them in hot, but not boiling, water. She soaked a soft linen cloth in the infusion.

I knelt in front of the boy, who was still trembling, wrapped in our thickest quilt by the hearth. “This is going to be warm,” I whispered, not knowing if he could even hear me. “It’s just to help you relax.”

I gently pressed the warm, damp cloth over his eyes and temples.

He flinched violently, letting out a small, trapped sound, like a cry that had been suffocated. He recoiled, but I held firm, my touch gentle but insistent.

“Shh, shh, it’s okay. You’re safe here. It’s just warm water and flowers,” I murmured.

Slowly, agonizingly slowly, the rigidity in his shoulders eased. The tremors didn’t stop, but they lessened. He was still a million miles away, locked inside himself, but for the first time since I’d found him, his body seemed to register a sensation. Warmth. Safety.

And so began the strangest, most terrifying week of my life.

We called him Daniel. We had to call him something. He never spoke. He never reacted.

We’d feed him broth, and it would just dribble out of his mouth unless we gently massaged his throat to make him swallow. He was a ghost in our cabin.

I would talk to him. I talked to him for hours. I told him about the trees, about the sound the wind makes through the pines, about the smell of bread baking in our wood-fired oven. I described the colors of the sunrise he couldn’t see.

“It’s pink, Daniel,” I’d say, holding him (still wrapped in blankets) by the one window that faced east. “It’s a soft, sleepy pink right now, like the inside of a seashell. And in a minute, it’s going to turn to fire. It’s going to be all gold and orange, and it’ll burn the fog off the mountain.”

Nothing.

Grams would work on his body. She’d rub his feet with warming oils—ginger and black pepper—to get his circulation back. She’d make him teas from lavender and skullcap to calm what she called “the storm in his nerves.”

On the fourth day, I was sitting opposite him, mending a tear in my jacket. The cabin was quiet, just the tick-tick-tick of my needle and the crackle of the fire.

I was describing the color of the thread. “It’s a dark green, like the moss on the north side of the oaks. Not the bright, happy green of the new leaves, but a deep, old green. The kind of green that holds secrets.”

I glanced up. And I froze.

A single tear was rolling down his left cheek.

My breath caught. I put my sewing down, my hands shaking.

“Daniel?” I whispered.

He didnt move. But another tear followed the first. He was in there. He was in there and he was listening.

“Oh, Daniel,” I breathed, moving to kneel in front of him. “It’s okay. It’s okay to be sad.”

He didn’t make a sound. He just sat, perfectly still, as silent tears streamed from his ‘blind’ eyes. It was the first sign of life. The first crack in the ice.

From that moment, everything changed. He was still silent, still ‘blind,’ but he was present.

I started teaching him to feel the world. I’d put a pinecone in his hand. “Feel that?” I’d say. “That’s a Ponderosa pine. It’s rough, but it’s strong. It smells like vanilla and sunshine.”

I’d guide his hand to knead the bread dough. “This is life,” I’d tell him. “It’s warm and soft and it’s growing.”

I took him outside, describing every step. “We’re on the porch, Daniel. The wood is old under your feet. Listen. Can you hear the chickadees? They sound like they’re saying their own name. Chick-a-dee-dee-dee.”

He was learning to see with his hands, his ears, his nose. He was slowly, painstakingly, coming back to life.

And then, on the seventh day, the world ended.

It wasn’t a sound I recognized. It was a low, mechanical rumble. It wasn’t our old Ford truck. This was a different beast.

I looked out the window. And my blood turned to ice.

A black Escalade, gleaming like an obsidian knife, was murdering the quiet of our gravel road. It was followed by another.

They parked, and the doors opened.

Part 2

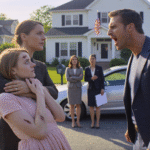

Two men stepped out of the first car. They wore black suits. Not just nice suits. Immaculate suits. Sunglasses. Earpieces. The kind of men you only see in movies, the kind you pray never to meet.

A third man stepped out of the second car. He was older, and his suit was different. Gray. Impossibly expensive. His face was granite.

“Grams,” I said, my voice a hoarse whisper. “Go to the back room. Lock the door.”

“Emily, what…?”

“Do it, Grams! Now!”

She saw my face, and she moved.

I grabbed the old shotgun from over the mantle. It was loaded with rock salt. Enough to sting, not to kill.

I stood on the porch as they approached.

“This is private property,” I called out, trying to keep the tremor from my voice. The shotgun felt heavy and useless.

The man in the gray suit didn’t stop. He walked right up to the bottom step, the two human walls in black suits flanking him. He took off his sunglasses. His eyes were the same color as his suit. Cold, dead gray.

“Where is he?” His voice was a low growl. Not a question. A demand.

“I don’t know who you’re talking about,” I lied.

He smiled, but it was the most terrifying expression I’d ever seen. It didn’t touch his eyes.

“You are Emily. You live here with your grandmother, a practitioner of ‘folk medicine.’ We’ve been tracking my son’s phone, which has been powered off. But the GPS in his shoe,” he tapped his own leather-clad foot, “has been pinging this exact location for 72 hours. So, I will ask one more time. Where is my son, Daniel Harrington?”

My heart stopped. Harrington. As in, Harrington Capital. The man who owned half of Seattle. The man who tore down forests to build glass towers.

I looked back, through the window. Daniel was sitting by the fire, just a small shape in a blanket. He seemed to be listening, his head tilted.

“He’s a patient,” I said, my voice shaking but defiant. “He was hypothermic. He’s… not well.”

“My son is not ‘unwell,’” Mr. Harrington sneered. “He is ‘non-responsive.’ A condition his ten-thousand-dollar-an-hour specialists in Manhattan have been unable to treat. And you think you can, with… what?” He gestured at the cabin, at the hanging herbs. “Dirt and leaves? Voodoo?”

The two guards moved, stepping onto the porch. I raised the shotgun. “Get back!”

Harrington laughed. A real, barking laugh. “Cute. Section 148, California… oh, wait, we’re in Washington. Section 9A.52.080. Criminal trespass. But I have a better one. Kidnapping. A federal offense. Especially when it’s the son of a man who has the Attorney General on speed dial.”

He took a step closer. “Give me my son, girl. Or the next people who come up this road will be wearing uniforms, and they will not be as polite as I am.”

I was trapped. I was a 26-year-old girl with a shotgun full of salt against a man who could buy the state.

“He’s scared,” I whispered, a final, desperate plea. “You can’t just… take him. He’s just… he’s just starting to come back.”

“He’s a broken asset,” Harrington said, his voice flat. “He’s being transferred to a new facility. A clinic in Switzerland. They have… different methods.”

One of the guards moved past me, brushing me aside as if I were a cobweb. I heard Grams yell from the back room. The guard pushed open the cabin door.

“No!” I screamed.

I ran inside. The guard, a mountain of a man, was already at Daniel’s side. He was unhooking a high-tech-looking medical device from his belt.

“Vitals are stable, sir,” the guard said into his wrist.

Mr. Harrington walked in, his expensive shoes clicking on our old pine floors. He looked around the cabin with utter disgust. “Pathetic.”

He walked over to Daniel. He didn’t kneel. He just looked down at him. “Daniel. Get up. We are leaving.”

Daniel, of course, didn’t move. He was frozen again, but this time, it was a different kind. It was the rigid terror of a rabbit under a hawk’s shadow.

The guard reached down, his hands impersonal and rough. He was going to just… package him.

“Don’t!” I shouted. “You’ll hurt him! You’ll undo everything! Let me.”

Harrington stared at me. He nodded. Once.

I dropped to my knees in front of the boy. The men, the father, the whole cold, cruel world disappeared. It was just me and Daniel.

I took his small, cold hands. “Daniel,” I whispered, my voice breaking. “These men… they’re here to take you back to your father.”

He didn’t move.

“I… I can’t stop them.” Tears were streaming down my face now. “But I need you to know. You’re strong. What we found… that light you’re feeling? That’s yours. No one can take that away from you. The world is full of color, Daniel. It’s full of life. Don’t let them make you forget.”

I squeezed his hands. “I know you’re in there. And I know you’re scared. But you have to be brave.”

The guard cleared his throat. “Sir, we have a window.”

Harrington nodded. “Take him.”

The guard scooped Daniel up, blankets and all. He was just a small, limp bundle in the arms of a giant.

They moved toward the door. I was sobbing, helpless.

As they passed me, Daniel, who had not moved or spoken in a week, suddenly turned his head toward me. His ‘blind’ eyes were wide. They were still unfocused, but they were searching.

And then, his voice, a tiny, rusty whisper I almost didn’t hear.

“I… I see…” he stammered.

My heart stopped. Harrington stopped. The guards stopped.

“What did he say?” Harrington demanded.

Daniel’s face was turned toward me, toward the lamp I had lit on the table. The warm, yellow light.

His eyes, for the first time, flickered. And then… focused. On the lamp.

“I see…” he whispered again, stronger this time. “I see the light.”

A strangled sound came from Harrington. It might have been a sob.

The guard just looked at his boss, waiting for orders.

Harrington composed himself instantly. His face became granite again. “A coincidence. A reflex. Get him in the car.”

And just like that, they were gone.

They walked out the door, put him in the black SUV, and disappeared down the gravel road, leaving a cloud of dust and silence behind them.

I collapsed onto the floor. Grams finally got the door unlocked and came running, holding me as I cried.

The cabin felt empty. The light he had seen was still flickering on the table, but the world had never felt so dark.

A year passed. 365 days.

The cabin was too quiet. Every time I heard a twig snap, I thought it was him. Every time a car engine rumbled in the far-off distance, my heart would leap into my throat, thinking it was the black Escalade returning.

I fell into a dark place. I doubted everything. What good was my “healing” if the world could just walk in and steal it? Grams’s words were… “You didn’t fail him, Em. You gave him a match in a pitch-black cave. What he does with that light is up to him. And God.”

But I felt like I’d failed. I’d shown him a spark, only to have him dragged back into the dark. I didn’t know if he was alive. I didn’t know if he was in Switzerland, or locked in a sterile room, or if the light I’d seen had been snuffed out for good.

Life went on. The seasons turned. The bitter cold of that October faded into the deep, wet snow of winter, which melted into the explosive, defiant green of a Cascade spring. The summer was hot and dry. And then, it was October again.

The anniversary.

I was chopping wood, taking my grief and fear out on the old pine rounds. Thwack. Thwack. Thwack.

I heard the car.

I froze. My axe still in my hand.

It wasn’t a rumble. It was a quiet whir.

A car was coming up our road. A blue Tesla. It was modest, quiet, and splattered with mud from the drive.

It pulled to a stop right where the Escalade had been.

The driver’s door opened, and a man got out.

It was Mr. Harrington.

But it wasn’t. The gray suit was gone. He was wearing… jeans. A simple button-down shirt, rumpled at the elbows. His face was… tired. He looked older. He looked… humbled.

I didn’t move. I just stood there, axe in hand.

He saw me. He raised a hand, palms out. “Emily. Please. I… I come in peace.”

I didn’t lower the axe. “You have five seconds to tell me why you’re on my property before I call the sheriff. And this time, it’s not loaded with salt.”

He winced. “I deserve that. I deserve… all of that. I’m not here to… I’m here to apologize.”

I laughed, a harsh, bitter sound. “Apologize? You don’t get to apologize.”

“You’re right,” he said, his voice quiet. He looked at the ground. “I was… a monster. I was a father, terrified, and I acted like a brute. I took him from you.”

“Where is he?” I demanded, my voice breaking. “Is he okay?”

“He is,” Harrington said, and this time, his voice did break. A tear rolled down his cheek. He wiped it away, angry and embarrassed. “He is.”

“The clinic in Switzerland… it was a disaster,” he continued, staring at the trees. “Sterile rooms, drugs, analysts. They put him in sensory deprivation tanks. They tried to ‘force’ a breakthrough. He got worse. He went… catatonic. He wouldn’t eat. He was… fading. They told me to prepare myself.”

I felt my knees go weak. I leaned the axe against the woodpile.

“One night,” he said, “I was sitting by his bed. Just… waiting for the end. And I was… I was humming. I don’t even know why. Just this… stupid tune.”

“And a nurse came in. She said, ‘What is that?’ I said, ‘I don’t know. Just… something.’ And she said… ‘He’s… his heart rate is changing. His brainwaves…’ She pointed to the monitor. ‘Keep doing it.’”

“So I kept humming. I hummed all night. And the next morning, Daniel… he… he squeezed my hand.”

“I didn’t understand. And then… I remembered. On the drive from your cabin to the jet… you were humming. I heard it on the recording from the security detail’s bodycam. You were humming to him as you knelt in front of him. That same tune.”

I hadn’t even realized. It was an old folk melody Grams always hummed.

“I… I fired them,” Harrington said. “I fired all of them. The Swiss doctors, the specialists. I took him home. Not to the glass tower in Seattle. I bought a house. In the country. With… trees. And I… I just… I talked to him. Like you did. I described the… the colors. The trees. The… chickadees.”

He looked at me, his eyes pleading. “It took… six months. But he’s… he’s back, Emily. He’s back.”

“And… his eyes?” I whispered.

“His… his specialists… they call it ‘Functional Neurological Disorder.’ Psychosomatic. The trauma of his… of my… of his mother’s death… it made his brain… just… turn off his vision. A fuse blew. They said he might never see again.”

“But…?” I prompted, holding my breath.

“But…” Harrington smiled. A real smile. “He’s stubborn. Like someone else I know.”

He turned to the car. “You can come out now, son.”

The passenger door of the Tesla opened.

And he stepped out.

He wasn’t the small, ghost-like boy. He was taller. His cheeks had color. He was wearing a simple red t-shirt and jeans.

He stood by the car, looking around. His eyes, bright and clear, scanned the trees, the cabin… and then landed on me.

A grin spread across his face.

“Emily!” he shouted.

And he ran.

He sprinted across the gravel, his legs pumping, and he didnV’t just hug me. He crashed into me, wrapping his arms around my waist so hard he nearly knocked me over.

“I saw you!” he yelled into my shirt, his voice muffled. “I saw you! You’re wearing a blue jacket!”

I was. A faded, denim blue.

I burst into tears, clutching him, burying my face in his hair. He was warm. He was real. “You’re seeing,” I sobbed. “You’re really seeing.”

“I am!” he said, pulling back, his face beaming. “I see the trees! And the smoke from the chimney! And Grams! She’s in the window!”

I looked up. Sure enough, Grams was at the window, tears streaming down her own face.

Harrington walked over, his hands in his pockets. He looked… peaceful.

“He… he wouldn’t stop talking about you,” Harrington said. “He wanted to come back. He needed to. To… to say thank you.”

“I’m the one who’s thankful,” I said, wiping my eyes, my hand still on Daniel’s head.

“I… I came to offer you a job,” Harrington said, looking awkward. “I’m… I’m building a new kind of clinic. A wellness center. Based on… this.” He gestured to the cabin, the woods. “Holistic. Compassionate. No ‘assets.’ Just… people. I want you to run it.”

I looked at the cabin. I looked at Grams. I looked at Daniel.

I smiled. “Thank you, Mr. Harrington. That’s… an incredible offer. But I can’t.”

He looked stunned. “But… why? I’ll pay you anything.”

“My place is here,” I said, squeezing Daniel’s shoulder. “With the people who need this. The ones who can’t afford a clinic in Switzerland. The ones the world forgets.”

Harrington stared at me for a long moment. Then, he nodded. He understood.

“I’ll… I’ll fund it,” he said. “Your… your work. Here. Whatever you need. A new roof. A new truck. A lifetime supply of… whatever it is you do.”

“We do just fine, Mr. Harrington,” Grams said, stepping out onto the porch with a tray. “But we’d be happy to accept a new roof. And you’ll stay for dinner.”

It wasn’t a question.

That night, the four of us ate at our small table. A billionaire, a ‘miracle’ boy, an old herbalist, and me.

As the sun set, Daniel grabbed my hand. “Come on!”

He pulled me outside, onto the porch. The sky was turning that deep, impossible purple it only does in the mountains.

“It’s my favorite,” he whispered, pointing at the sky. “You were wrong about the sunrise.”

“I was?” I laughed.

“Yeah. The sunset is the best. It’s not pink. It’s… it’s everything.”

He was right. It was.

He promised he’d come back every summer. He has. He’s 14 now. He calls Grams “Grams.” He helps me check the traplines.

The locals, they heard the story. They still call me the “miracle girl.” But I’m not. I didn’t perform a miracle.

I just… listened. I offered a little warmth, a little light, in a world that had gone cold and dark. Sometimes, that’s all the magic you need.